If the president of the United States goes on record to praise a tour destination as beautiful or amazing, I would be inclined to mention it on tour.

So as the EF Tour Director for a group of fellow North Americans, it was from that angle that I introduced our imminent visit to the Alhambra—the 13th-century Moorish palace built into the hills overlooking Granada, Spain.

Microphone in hand, I readied an excerpt from Bill Clinton’s My Life (my group was Canadian, so I felt relatively assured that a mention of Mr. Clinton wouldn’t spark a partisan flare-up on the bus) and unleashed the following quote on them:

“I never got over the romantic pull of Spain, the raw pulse of the land, the expansive, rugged spirit of the people, the haunting memories of the lost civil war, the Prado, the beauty of the Alhambra. When I was President, Hillary and I became friends with King Juan Carlos and Queen Sofia. (On my last trip to Spain, President Juan Carlos had remembered my telling him of my nostalgia about Granada and took Hillary and me back there. After thirty years I walked through the Alhambra again, in a Spain now democratic and free of Francoism, thanks in no small part to him.)” [Clinton, My Life, 172]

The group perked up, either owing to the content of the message or the fact that I delivered it in my best Bill Clinton voice.

The episode got me thinking of two things. One: Even someone as

smooth as Bill Clinton can screw up the titles of foreign dignitaries

(in the second name-drop, Clinton misidentifies Juan Carlos as

“President”); and two: Gee, how many other presidential travel

endorsements could I drum up?

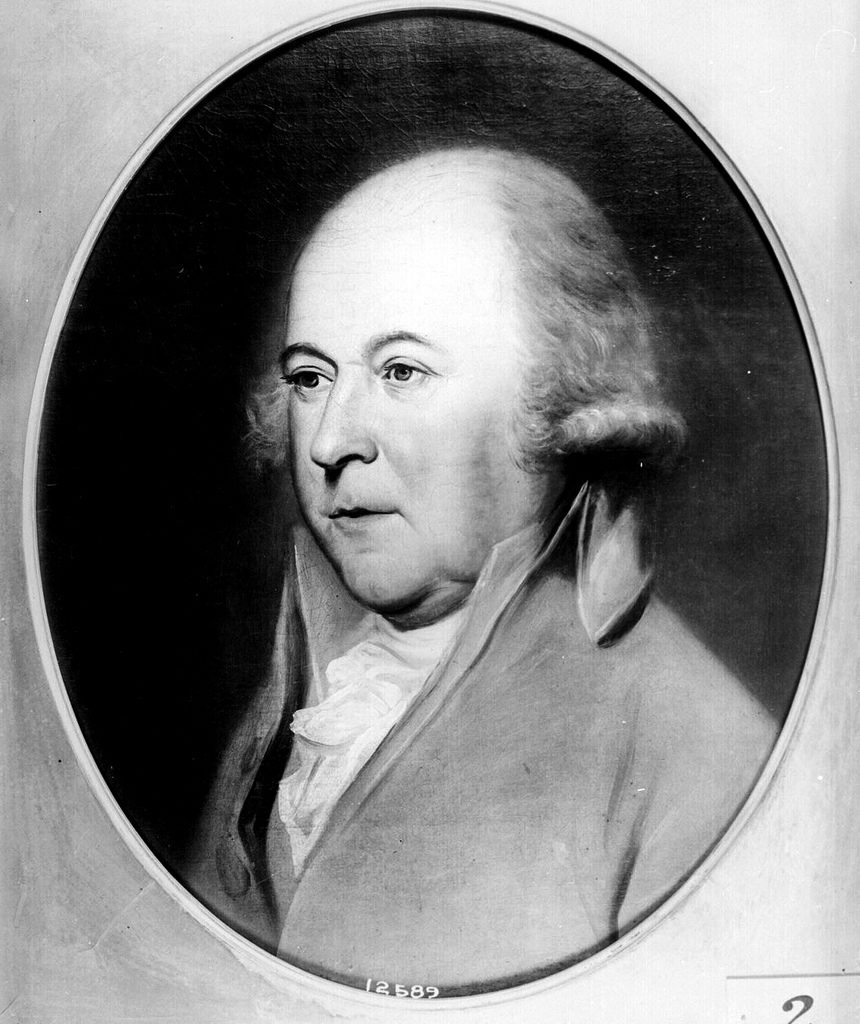

My mind went directly to John Adams, the second U.S. president, and to one of my favorite books, John Adams, the Pulitzer Prize-winning biography by David McCullough. It’s

rich with excerpts of letters Adams wrote home from Europe, where he

was posted to secure French and Dutch help against the British in the

then-ongoing Revolutionary War.

It’s true that this 200-year backtrack takes me rather dramatically

from one end of the presidential bookshelf to the other—from President

No. 42 (Bill Clinton) all the way back to No. 2 (Adams). But in any

event, there wouldn’t be too many other stops along the shelf if one

were looking for presidential firsthand appraisals on life in

Europe—No. 3 Thomas Jefferson, No. 6 John Quincy Adams and No. 35 John F. Kennedy are

really the only other U.S. presidents who lived in Europe

(excluding, for our purposes here, those like No. 34 Dwight Eisenhower, who

clearly experienced Europe, but only as a battlefield).

And so all the way back to Adams’ perspective we go. And we’re lucky

to have such a window on Europe, because Adams’ time there—the late

1770s and early 1780s, i.e., just after America’s 1776 premiere—make

his among the very first truly “American” insights and thoughts on

Europe.

If in 2008 we Americans complain of multi-leg flights, long layovers and delays,

consider the American traveler of 1778. Departing Boston on February 13

of that year, John Adams and his son John Quincy Adams (future U.S.

President No. 6) didn’t arrive in Bordeaux, France, until April 1.

That’s 48 days of travel—in other words, about four times the length of

the entirety of a typical EF tour to Europe, and that was just getting there. Adams later wrote about the voyage:

“No man could keep upon his legs, and nothing could

be kept in its place. The wind blowing against the current … produced

a tumbling sea, vast mountains, sometimes dashing against each other …

and not infrequently breaking on the ship, threatened to bury us all at

once in the deep. … The noises were such that we could not hear each

other speak at any distance.” [McCullough, John Adams, 182].

Of course, once at port, it would take four more days over land

before Adams reached Paris. So perhaps the 2008 definition of “long

airport transfer” could benefit from some perspective? Adams’ journal

entries:

April 5, Sunday

“Proceeded on our journey, more than 100 miles.”

April 6, Monday

“Fields of grain, the vineyards, the castles, the

cities, the gardens, everything is beautiful. Yet every place swarms

with beggars.”

April 8, Wednesday

“Rode through Orleans and arrived in Paris about nine

o’clock. For thirty miles from Paris or more the road was paved, and

the scenes were extremely beautiful.” [McCullough, 188]

Finally in Paris, Adams spent his first nights at a hotel on the Rue

de Richelieu—where he was dumbstruck by the ‘glittering clatter’

(Adams’ phrase) of huge crowds and countless carriages on the Parisian

streets. In a letter to his wife, Abigail, he gushed:

“The delights of France are innumerable. The

politeness, the elegance, the softness, the delicacy is extreme. … The

richness, the magnificence, and splendor is beyond all description. …

If human nature could be made happy by anything that can please the

eye, the ear, the taste or any other sense, or passion or fancy, this

country would be the region for happiness.” [McCullough, 192]

Perhaps by only modernizing the words a bit, we’d have the typical 2008 postcard text written after a busy day’s touring.

And just like that 1-in-100 tour group that happens upon a celebrity

sighting on tour (say, Kevin Spacey in London), Mr. Adams stumbled

across a whopper of a historical figure—the French Enlightenment writer

and philosopher Voltaire, then 83 and in the last month of his life.

Adams wrote of it:

“Although he was very advanced in his age, had the

paleness of death and deep lines and wrinkes in his face … [his eyes

possessed a] sparkling vitality. They were still the poet’s eyes with a

fine frenzy rolling.” [McCullough, 195]

If that wasn’t impressive enough, then imagine sending this postcard to the folks back home:

“She was an object too sublime and beautiful for my

dull pen to describe. … She had a fine complexion indicating her

perfect health, and was a handsome woman in her face and figure. … The

Queen took a large spoonful of soup and displayed her fine person and

graceful manner, in alternatively looking at the company in various

parts of the hall and ordering several kinds of seasonings to be

brought to her, by which she fitted her supper to her taste.” [McCullough, 203]

That was John Adams, reflecting on his meeting Marie Antoinette on May 8, 1778.

Adams would make the transatlantic trip several times. On a

subsequent trip across the Atlantic, winds blew the ship off its

France-bound course, landing the passengers instead at the northwest

tip of Spain, just above La Coruña. From there, he and his party would

travel by mule, passing through Burgos and Bilbao on the way to the

Pyrenees and the French border (where they would go by carriage to

Paris). Adams remarked on the Picos de Europa (jagged mountain peaks

just off Spain’s northern coast):

“There is the grandest profusion of wild irregular mountains I ever saw.” [McCullough, 230]

And of the Spanish taverns along the way, and by extension, Spanish daily life in 1779:

“We got nothing at the taverns but fire, water … and

sometimes the wine of the country. … Smoke filled every part of the

kitchen, stable, and other part[s] of the house, as thick as possible

so that it was … very difficult to see and breathe. … The mules, hogs,

fowls and human inhabitants live … all together. … Nothing appeared

rich but the churches, nobody fat but the clergy.” [McCullough, 230]

Despite the hardships of the journey, Adams’ inner tourist was alive

and well—not to mention well-informed and ultimately

frustrated—because, according to McCullough, upon leaving Spain, Adams

specifically regretted not having the chance to visit the cathedral of Santiago de Compostela, end-point of the famous pilgrimage route.

After another stint in Paris, Adams was sent north to Holland. In

Amsterdam, he giddily engaged in cultural compare-and-contrast (as

every model EF traveler should do), measuring the Dutch against the

French and others:

“Their industry and economy ought to be examples to

the world. They have less ambition, I mean that of conquest and

military glory, than their neighbors, but I don’t perceive that they

have more avarice. And they carry learning and the arts, I think, to a

greater extent.” [McCullough, 247]

But there’s always room for valid criticism from a visiting

foreigner, for rarely is touring all rose petals and no rough edges.

Adams described the Amsterdam air as “not so salubrious,” and he was

right; the Amsterdam canals were famously filthy in the 18th century,

and the contaminated and foul-smelling water was the culprit for a

frequently striking illness that was known at the time as “Amsterdam

fever” [McCullough, 246/7].

Perhaps there is a unbridgeable difference between Adams’ touring

and our student groups’ touring—after all, we often go on tours and

merely see the stage on which a long-ago history took place, while

Adams seems to have been one of the actors performing alongside the

stars. There’s even an institute in Amsterdam named after him; doubtful one of us typical EF travelers would garner a similar honor.

But maybe Mr. Adams wasn’t so different from us after all. While at

Amsterdam, Adams visited the nearby city of Leiden, where the English

who fled religious persecution in 1609 (and who would later become

known as the Pilgrims) stayed during the 11 years before their

Mayflower set sail and ultimately hit land at Massachusetts. Standing

before the Pieterskerk cathedral, a structure that would have been a

central feature in the area the Pilgrims lived in some 170 years

earlier, an onlooker recorded that “Mr. Adams could not refrain from

tears in contemplating this great structure” [McCullough, 253].

Had it been possible, I dare say he’d have asked someone to take his picture in front of it.

Related articles