The following is an excerpt from Nobel Journeys, a story collection that chronicles the extraordinary lives of Nobel Prize Laureates from the past and present, from all over the world, and from every Nobel Prize category. All 10 stories focus on important moments of discovery in the Laureates’ lives that helped them choose their unique pathways to success. And every tale reinforces the notion that education is an essential ingredient to a bright future.

Nobel Journeys is the first of many joint initiatives from the Nobel Prize Museum and EF Education First, two global organizations dedicated to bringing learning to life for students. Download a free copy of the full book and accompanying lesson plan for your classroom, and show your students that great ideas can come from anyone, at any time.

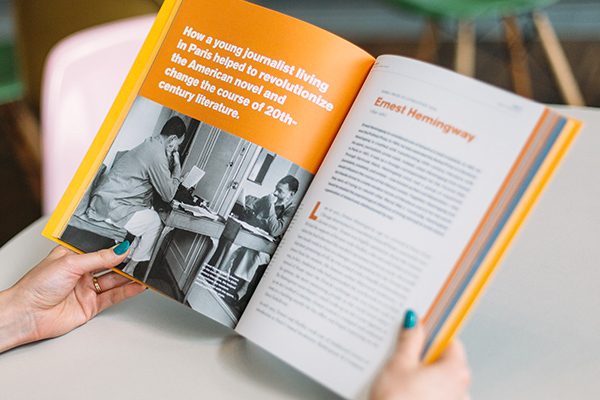

Ernest Hemingway is considered one of America’s best novelists. In 1951, he won the Pulitzer Prize. In 1954, he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature. Hemingway is credited with transforming 20th-century literature with his spare, journalistic prose style. Indeed, when Hemingway first moved to Paris in 1921, it was as a foreign correspondent for the Toronto Star. Through Gertrude Stein, Hemingway soon met a group of expatriate journalists, novelists, and artists – now known as the Lost Generation – who would influence the course of his literary career. Together, Hemingway and his friends strove to create modern forms of literature and art for the world they were all trying to rebuild after World War I. Ironically, Hemingway found he needed the psychological distance of living abroad to write about a generation of Americans disillusioned by war.

Late in 1921, Ernest Hemingway, age 22, arrived in Paris from Chicago determined to transform himself from a journalist into a fiction writer. Ernest was highly optimistic about the venture.

He had the support of his new wife Hadley, who not only believed in his talent but had inherited the needed trip money from an uncle. He would have steady work in Paris as a foreign correspondent for the Toronto Star. And most promising of all, he was armed with a bundle of introduction letters from his mentor, the famous author Sherwood Anderson. It was, in fact, Anderson who had persuaded the newlyweds to try Paris instead of Rome since the French exchange rate was better and, in his opinion, the most interesting people in the world lived there. The Hemingways soon found a small walk-up in the Latin Quarter at 74 rue du Cardinal Lemoine. Ernest rented a cramped and unheated room in a building nearby for his office and began reporting on the Greco-Turkish war.

In early 1922, Ernest and Hadley took one of Anderson’s letters of introduction to Paris’s famed bookstore Shakespeare & Company. Its American expatriate owner Sylvia Beach introduced them to the Irish writer James Joyce, who had just published his avant-garde novel Ulysses with her. (Hemingway and Joyce would soon become close friends and haunt several of Paris’s seedier expatriate bars together.) At Shakespeare & Company, the Hemingways also met English poet Ezra Pound, who built bookshelves for Beach on the side. Pound took an instant liking to them – he saw a promising young writer in Ernest– and suggested they all go for tea at Gertrude Stein’s house on the Left Bank. Stein ran a salon on Saturdays for artists, painters, poets, and novelists. The Hemingways were delighted to join him; one of Anderson’s introduction letters was, in fact, addressed to Miss Stein: “Mr. Hemingway is an American writer,” it read, “instinctively in touch with everything worthwhile going on here.”

Gertrude Stein welcomed the Hemingways with open arms, but they were quickly separated at the front door. Hadley and the other wives were taken to the parlor to be entertained by Miss Stein’s companion, Alice B. Toklas. All the artists and writers followed Stein to a large studio hung with canvases by avant-garde painters of the Montparnasse quarter. Here the group discussed what it meant to create art and literature after World War I. They were disillusioned with the generation that had nearly destroyed Europe. Since civilization now needed to be rebuilt, why not break from the past entirely to create a new cultural language – both verbal and visual – that reflected their generation’s modern values? Visual artists like Picasso, Miró, and Gris were finding inspiration in African and Asian art, multiple perspectives, and industry and speed. Poets like Apollinaire and Cocteau were inspired by innovations in visual arts, science, and politics.

Fascinated, Ernest Hemingway became a salon regular.

Stein happily took him under her wing. Ernest began to write short stories, and she was one of the first to read his early drafts.5) Stein’s initial feedback was not always glowing. Early on she advised him: “There is a great deal of description in this, and not particularly good description. Begin over again and concentrate.”

Ernest realized he was not creating a new language yet; he was just copying other writers – including Anderson – he admired. Ezra Pound had also become a mentor, but Ernest decided to emulate the poet’s lush prose less and less. Instead, he turned to the journalistic training he had received at the Kansas City Star, where he had taken a job straight out of high school. He used an unflinching observational eye to describe young American characters struggling to find their place in a post-war world. (Living abroad as an expatriate helped him to view American society with a new perspective.)

In Ernest’s first 20 months in Paris, he filed 88 stories for the Toronto Star. Many pieces chronicled Europe’s struggle to maintain stable peace. But others were pure travel articles on deep-sea fishing in Spain and the best trout fishing in Europe. Meanwhile, a stack of short stories also began to accumulate.

In 1922, the Hemingways went on an excursion to Pamplona, Spain, one that would change Ernest’s fortunes as a writer. They wanted to witness the San Fermin festival, and its running of the bulls through town to kick off the bullfights. Hemingway was captivated by the event: the color and pageantry, bravery and brutality. He and Hadley vowed to return to Pamplona the next year. But first they moved back to Toronto, so that Hadley could give birth to their first son, John Hadley, in 1923.

Ernest continued to write stories for the Star, but he found himself restless and bored, missing their expatriate life in Paris. He threw himself into his fiction writing. And thanks to the help of Sherwood Anderson, he even managed to publish his first book Three Stories and Ten Poems.

The Hemingways returned to Paris with their new son in 1924. They moved to a larger apartment on rue Notre-Dame des Champs – just down the street from Ezra Pound. And Ernest, determined to make a name for himself in the expatriate literary community, began working with Pound and novelist Ford Madox Ford to launch a new literary magazine called the Transatlantic Review. He continued to publish his own stories there, as well as in American literary magazines and

periodicals. Meanwhile, Ernest kept competitive tabs on other writers who were making a splash. One he admired was F. Scott Fitzgerald. In fact, it was reading the Great Gatsby, published to great acclaim in 1925, that galvanized his determination to write a novel – one that might, perhaps, be set at the San Fermin festival in Pamplona.

Little did Ernest realize he would run into his literary idol at Paris’s Dingo Bar a few months later. Ernest recognized Fitzgerald as soon as he strode through the doors with another man. He introduced himself and complimented Fitzgerald on his work. To Ernest’s surprise, Fitzgerald had already read and admired a few of his stories and had even sent them along to his editor at Scribner’s with a note stating, in his opinion, that Hemingway was the new voice of the 20th century. Fitzgerald flatly stated he was sure Hemingway’s work would outlast his own, and ordered a bottle of champagne. The two became fast friends and rivals for the remainder of their lives.

Hemingway did write a novel set in Pamplona. And it was indeed about a group of disillusioned expatriate Americans who travel to Spain to see the running of the bulls. Fitzgerald’s editor at Scribner’s published The Sun Also Rises in 1926 to worldwide acclaim. Hemingway went on to write several more award-winning novels in the same spare, observational way – always focusing on the “truth” of the story, rather than on its style. By doing so, he helped to transform the world’s notion of modern literature.

Download a free copy of the full book and accompanying lesson plan for your classroom.

Related articles