The following is an excerpt from Nobel Journeys, a story collection that chronicles the extraordinary lives of Nobel Prize Laureates from the past and present, from all over the world, and from every Nobel Prize category. All 10 stories focus on important moments of discovery in the Laureates’ lives that helped them choose their unique pathways to success. And every tale reinforces the notion that education is an essential ingredient to a bright future.

Nobel Journeys is the first of many joint initiatives from the Nobel Prize Museum and EF Education First, two global organizations dedicated to bringing learning to life for students. Download a free copy of the full book and accompanying lesson plan for your classroom, and show your students that great ideas can come from anyone, at any time.

“Let us pick up our books and our pens. They are our most powerful weapons. One child, one teacher, one book and one pen can change the world.” – Malala Yousafzai

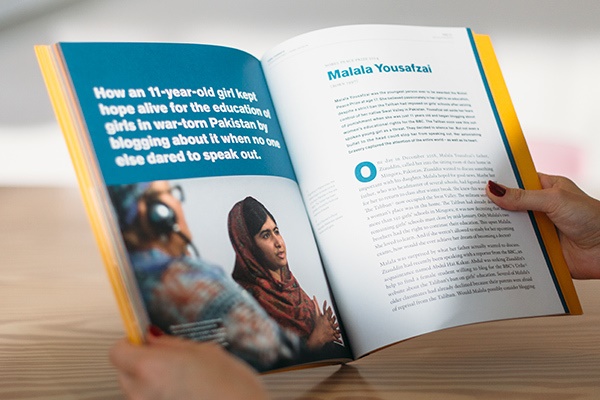

Malala Yousafzai was the youngest person ever to be awarded the Nobel Peace Prize at age 17. She believed passionately in her right to an education, despite a strict ban the Taliban had imposed on girls’ schools after seizing control of her native Swat Valley in Pakistan. Yousafzai set aside her fears of punishment when she was just 11 years old and began blogging about women’s educational rights for the BBC. The Taliban soon saw this out- spoken young girl as a threat. They decided to silence her. But not even a bullet to the head could stop her from speaking out. Her astonishing bravery captured the attention of the entire world – as well as its heart.

One day in December 2008, Malala Yousafzai’s father, Ziauddin, called her into the sitting room of their home in Mingora, Pakistan. Ziauddin wanted to discuss something important with his daughter. Malala hoped for good news. Maybe her father, who was headmaster of several schools, had figured out a way for her to return to class after winter break. She knew this was unlikely. The Taliban now occupied the Swat Valley. The militant sect believed a woman’s place was in the home. The Taliban had already destroyed more than 150 girls’ schools in Mingora; it was now decreeing that any remaining girls’ schools must close by mid-January. Only Malala’s two brothers had the right to continue their education. This upset Malala. She loved to learn. And if she weren’t allowed to study for her upcoming exams, how would she ever achieve her dream of becoming a doctor?

Malala was surprised by what her father actually wanted to discuss. Ziauddin had recently been speaking with a reporter from the BBC, an acquaintance named Abdul Hai Kakar. Abdul was seeking Ziauddin’s help to find a female student willing to blog for the BBC’s Urdu website about the Taliban’s ban on girls’ education. Several of Malala’s older classmates had already declined because their parents were afraid of reprisal from the Taliban. Would Malala possibly consider blogging for the BBC instead? She could use a pseudonym to protect her identity. And anyway, Ziauddin was certain no Muslim would ever harm a child. Malala immediately said yes.

Malala didn’t agree with the Taliban’s interpretation of Islamic law that “good” Muslim women should remain at home and not venture to the market, even, without dressing in a full burqa in the company of a male relative. She had studied the Quran herself, and nowhere could she find passages in it that directly banned women from going out in public, or attending school, or having jobs, or voting. (Why couldn’t she be a devout Muslim while still liking the color pink, listening to Justin Bieber songs, and watching Ugly Betty reruns on cable TV?) Malala wasn’t afraid to speak out. In fact, Malala had already given a speech on that very topic at Peshawar’s press club earlier that September: “How Dare the Taliban Take Away My Basic Right to Education.”

Besides, her father had named her after a strong Pashtun folk heroine, Malalai of Maiwind, who had inspired soldiers on the battlefield to victory by removing her veil and singing songs about bravery.

On January 3, 2009, Malala posted her first blog entry for BBC Urdu, called “Diary of a Pakistan Schoolgirl.” She had written the diary entry out by hand and called it in to Abdul on his wife’s cellphone, to avoid suspicion. She used the alias Gul Makai, the name of another strong girl character from Pashtun folklore. Malala blogged about the bad dreams she’d been having since the arrival of the Taliban’s helicopters and tanks in Swat. She blogged about how afraid she was to attend school now that it was banned for girls. She blogged about how sad it made her when fewer and fewer students dared to turn up for class.

For the next two months, she continued to blog in Urdu and English about how terrified she felt by the nightly gunfire between Taliban militants and the Pakistan Army. She wrote about how hopeful she felt when rumors of a ceasefire began to crop up. She described her joy when the Taliban announced they would let girls return to school to complete their exams – as long as they wore burqas. The popularity of her blog encouraged her to be even more outspoken. She decided to use her own name to speak out against the Taliban on a current affairs radio show called Capital Talk. Both she and her father agreed to be interviewed for a documentary on the Swat Valley conflict being filmed by the New York Times. But then rumors of a ceasefire abruptly ended, and the violence got much worse.

Malala and her family were forced to flee Mingora. Their home was looted. Ziauddin received death threats from the Taliban. This didn’t silence Malala. It only made her change her mind from wanting to be a doctor when she grew up to being a politician. She and her father even arranged to meet with Richard Holbrooke, a US envoy in the region, to plead in English for intervention. Malala said: “Respected Ambassador, if you can help us in our education, so [sic] please help us.” Eventually, the Taliban was forced by the Pakistan Army to retreat from Mingora to the hills. Malala’s family returned home. Though the city was now a bombed-out shell, Malala was relieved to find both her house and school intact. Overjoyed, she resumed her studies in August.

But she soon realized her life would never be the same.

By then the Times documentary had made Malala world-famous. It was no longer a secret that she had written “Dairy of a Pakistan Schoolgirl.” Again, she set aside her fear of the Taliban. She began to advocate publicly for girls’ education. In October 2011, she was nominated for the International Children’s Peace Prize. In November 2011, she won Pakistan’s first National Peace Award for Youth, and a local secondary school was named in her honor.

Malala began to receive death threats in the newspaper, on her Facebook page, slipped under the front door. Still she would not be silenced. To the contrary, she set her sights on establishing a foundation to provide poor girls with an education. She was 15 years old.

On October 9, 2012, Malala had just finished her day at school. She was boarding a small open-air bus with her best friend Moniba for the ride home. She was discussing a big test she had just taken with Moniba, when the bus suddenly jerked to a halt. A masked gunman stuck his head in the back and shouted, “Which one of you is Malala? Speak up, otherwise I will shoot you all.” Several pairs of eyes on the bus inadvertently darted to Malala. The gunman took aim and shot her in the head.

A week later, Malala woke up in a hospital. She had been in a coma for nearly a week. She had no idea what had happened to her, or where she was. She couldn’t speak or hear, so someone brought her an alphabet board. The first word she spelled out was “Country?” She was told she had been brought to a hospital in Birmingham, England specializing in head injuries. Her doctors informed her she was lucky to be alive. Her face was paralyzed, her hearing was damaged, her skull would need reconstructive surgery, and, after all that, she would need months of physiotherapy to walk properly again. Malala’s next word was “Father?” She was reassured Ziauddin and the rest of her family were on their way to England. They would all live temporarily in Birmingham while she recovered. One of Malala’s next questions was when she could go back to school.

It would be nearly five months before she could begin attending the all- girls’ Edgbaston High School in Birmingham. But within two years, Malala would be fully recovered, a Nobel Peace Prize Laureate, running the Malala Fund, and speaking about girls’ rights and children’s education all over the world. Yet she would still somehow find time to study for her university entrance exams and earn a string of A’s. And she would continue to speak out, no matter what.

Download a free copy of the full book and an accompanying lesson plan for your classroom.

Related articles